Article - Calligraphy.

Calligraphy.

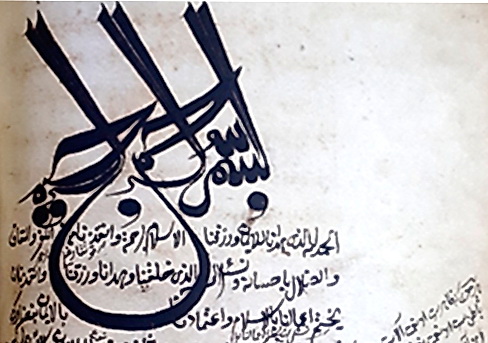

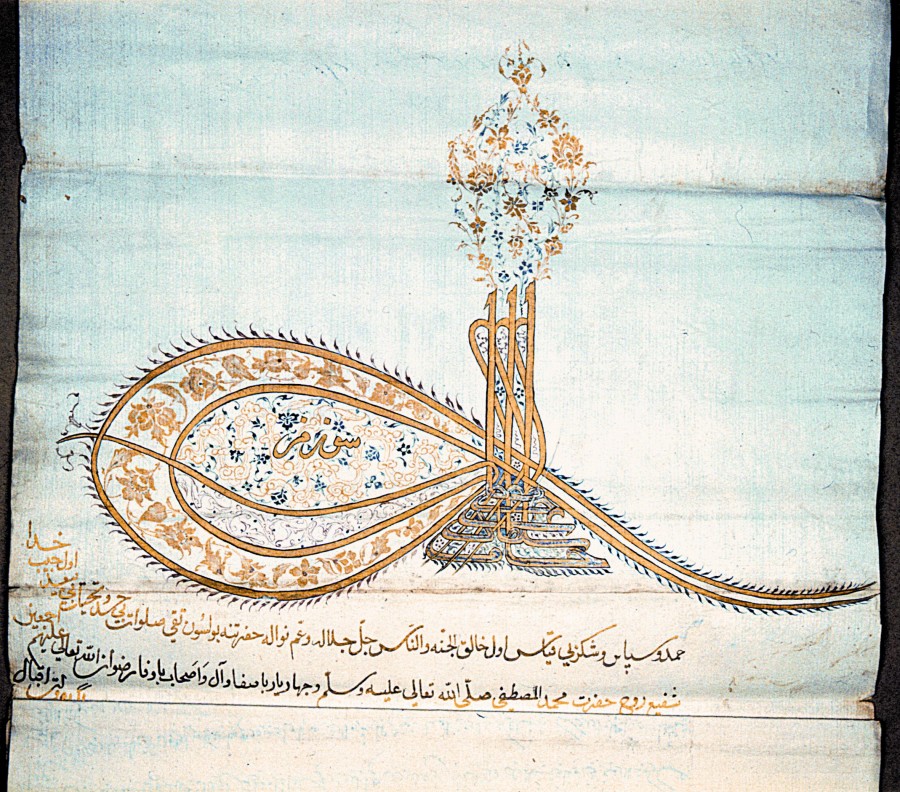

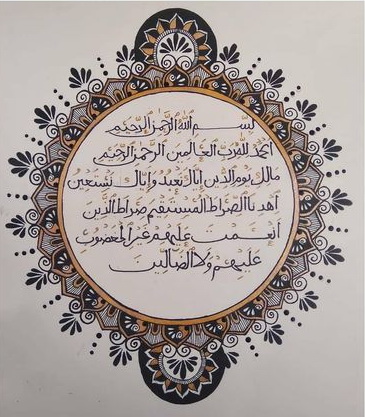

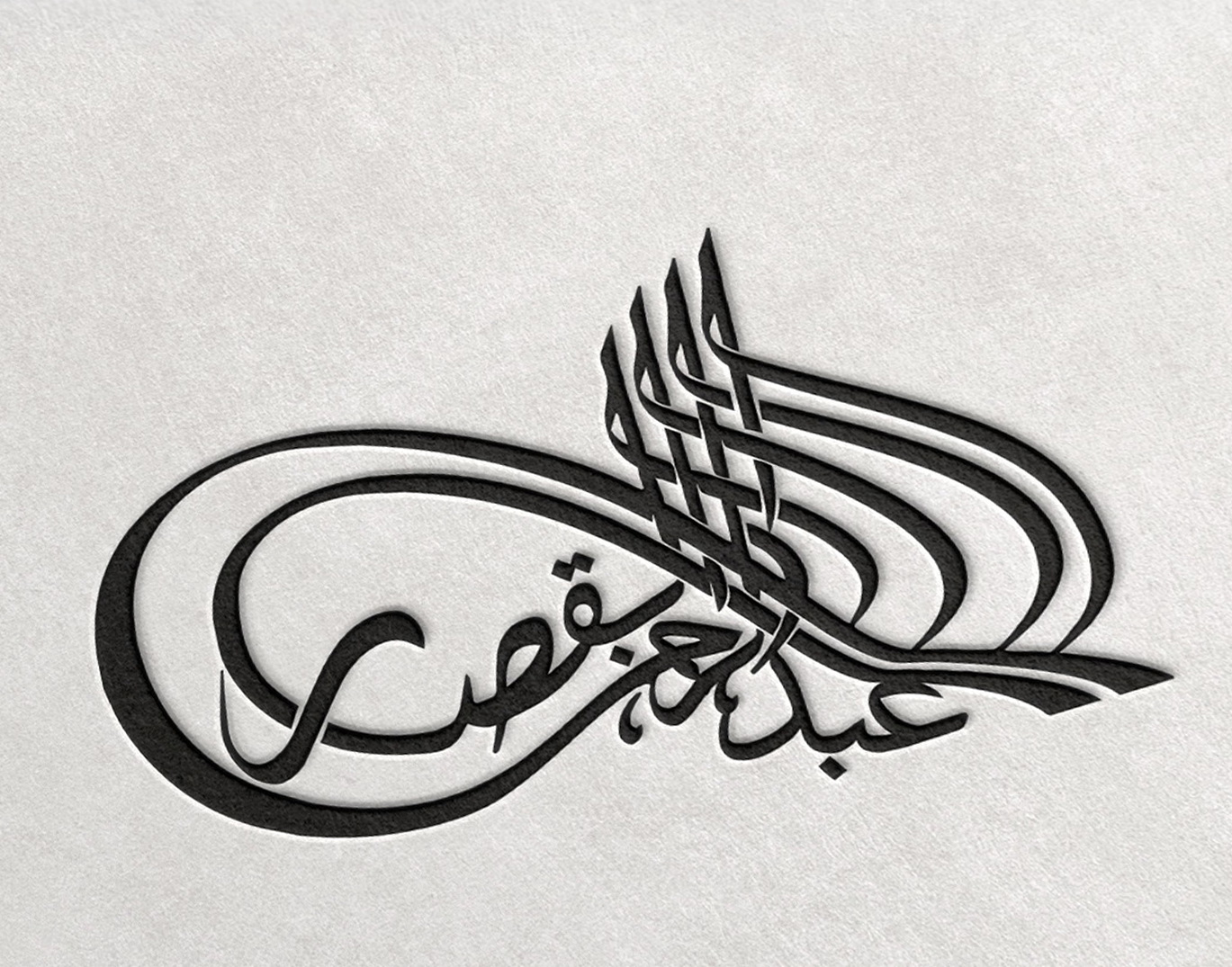

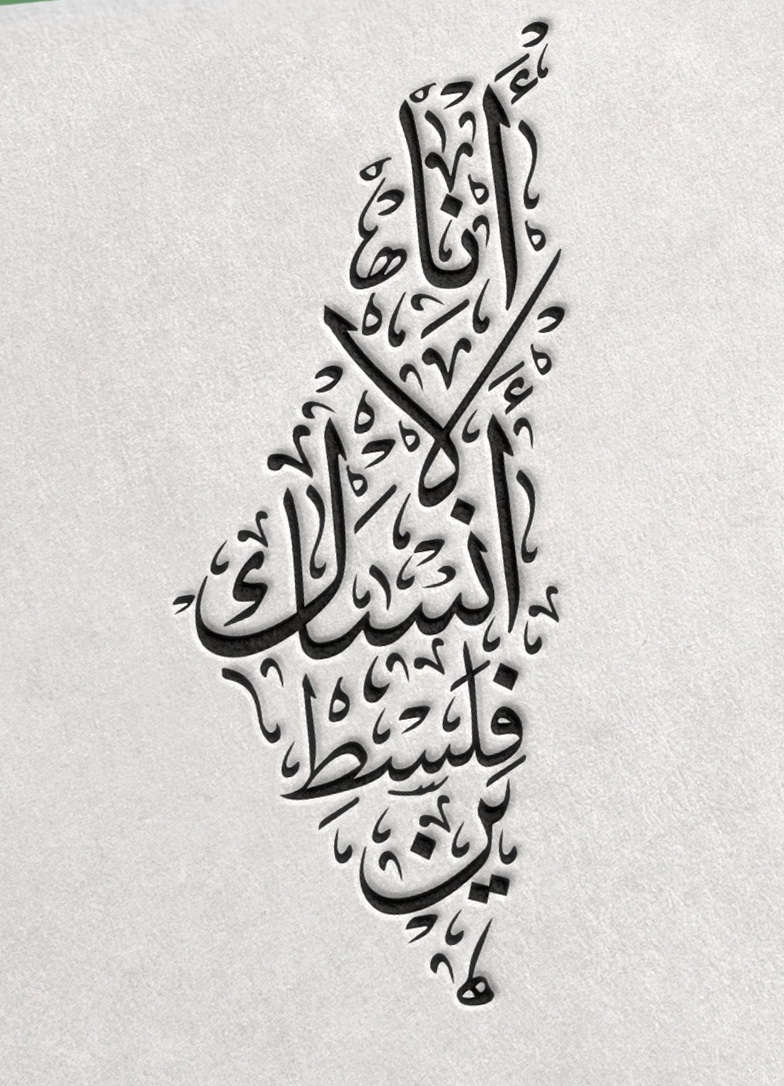

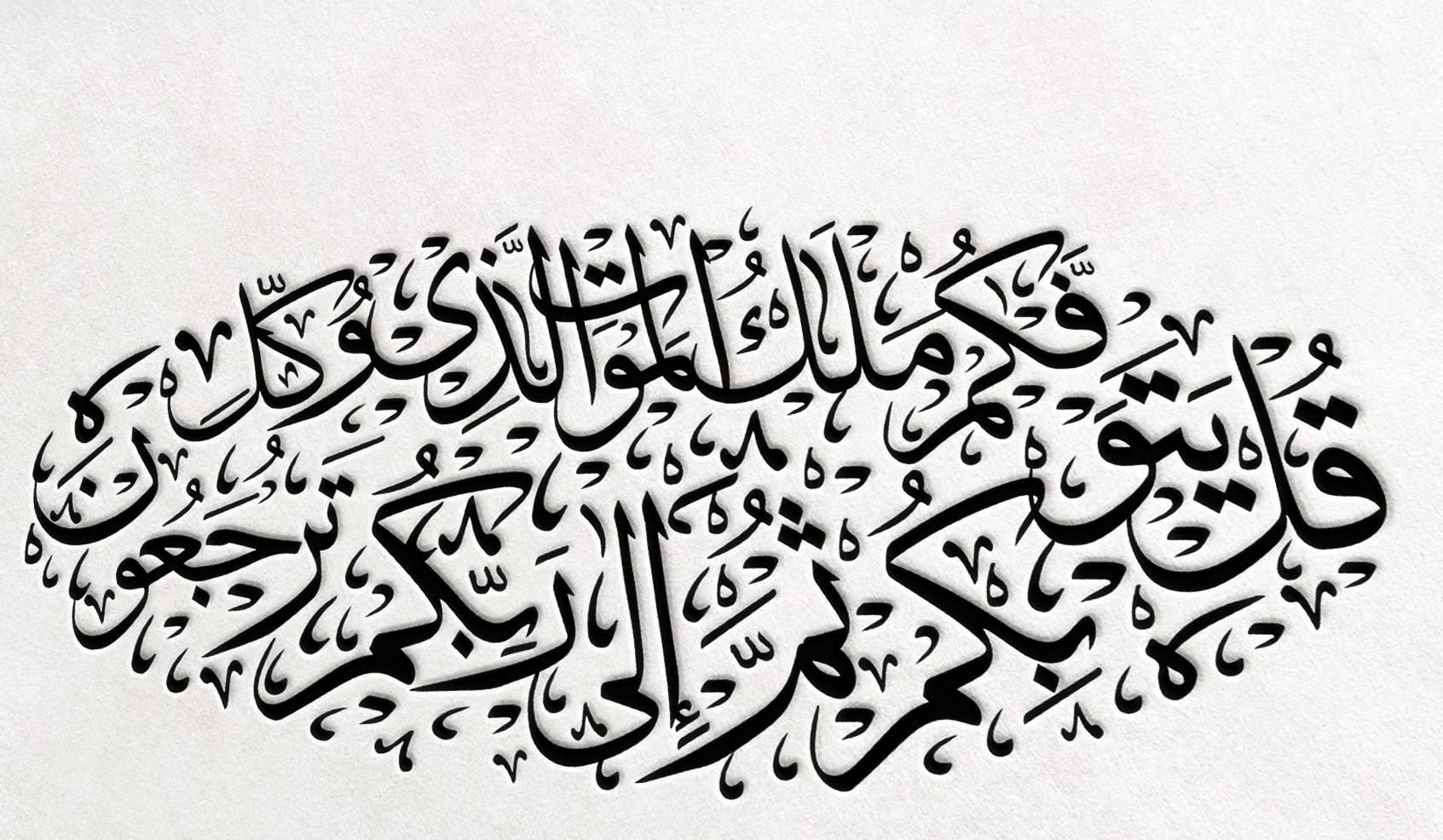

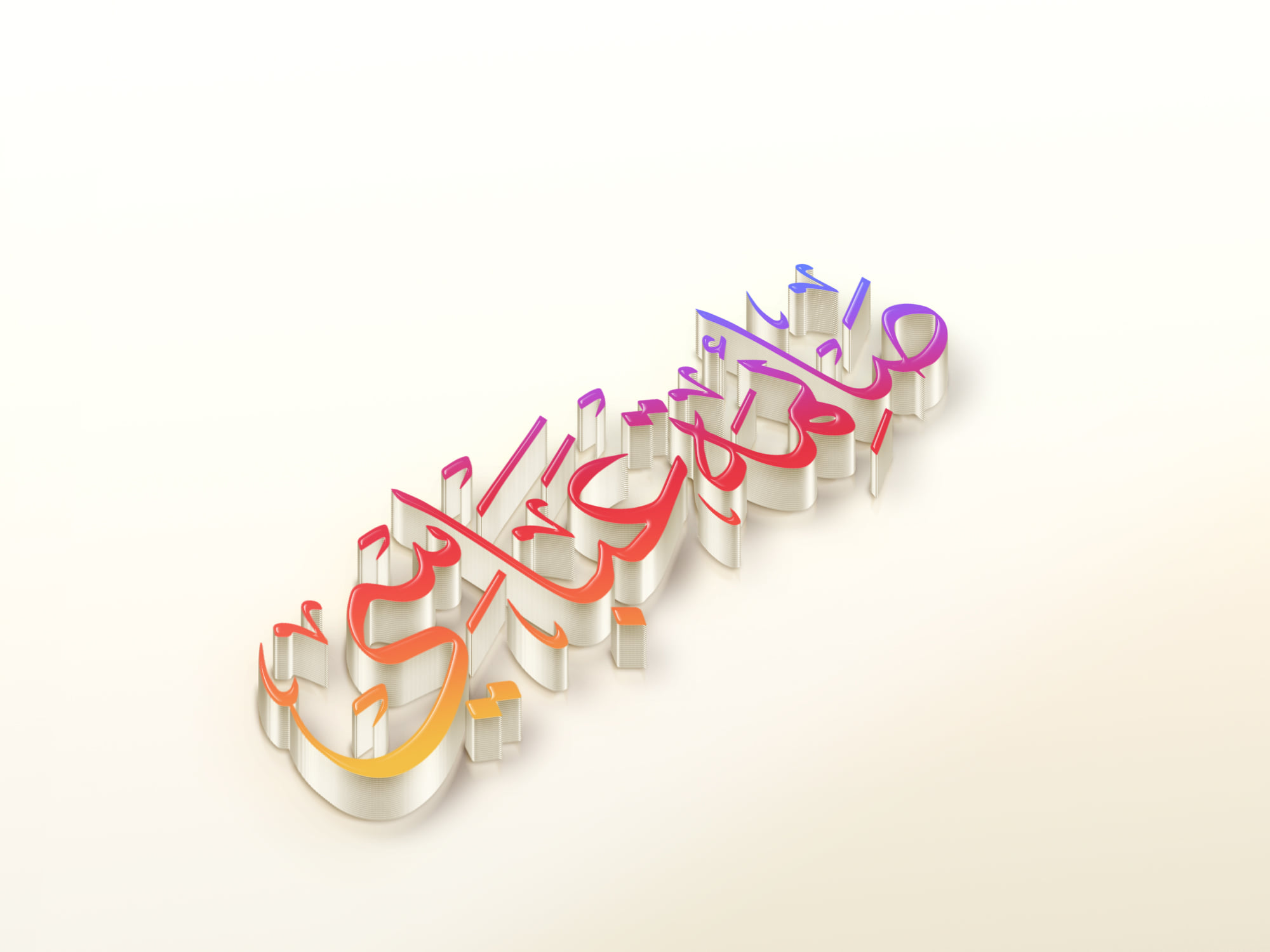

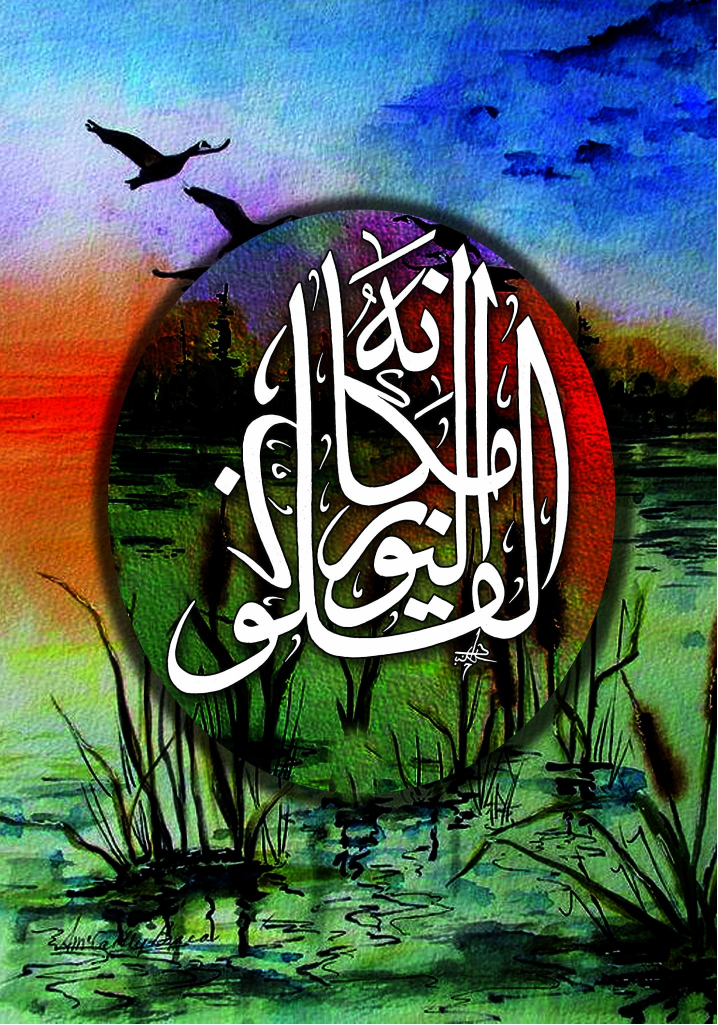

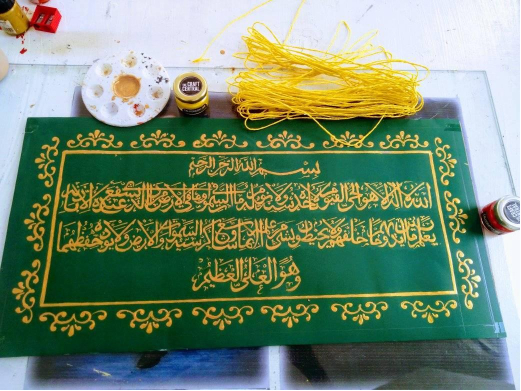

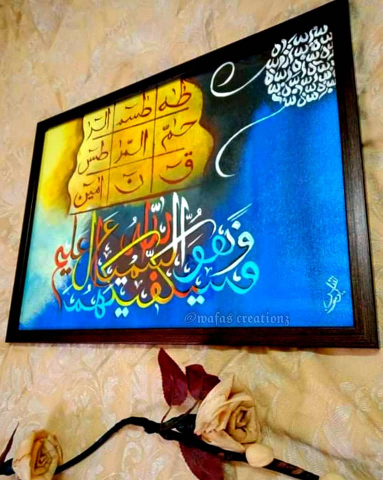

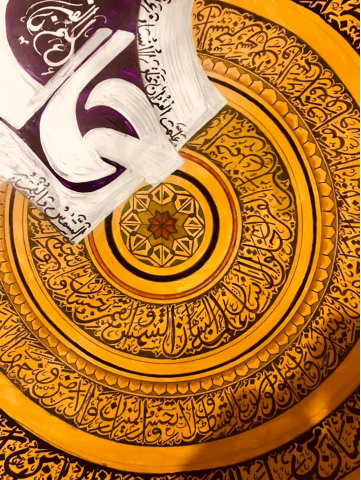

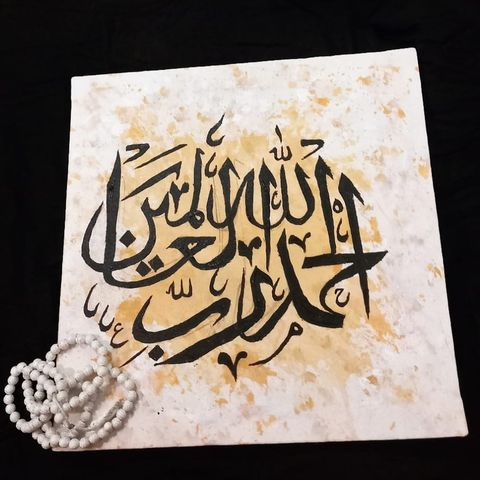

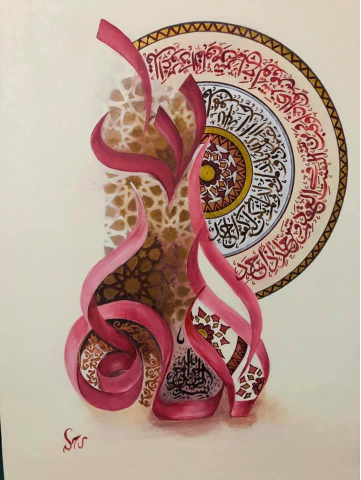

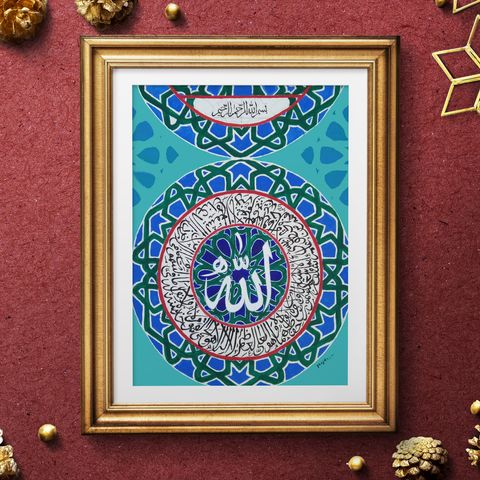

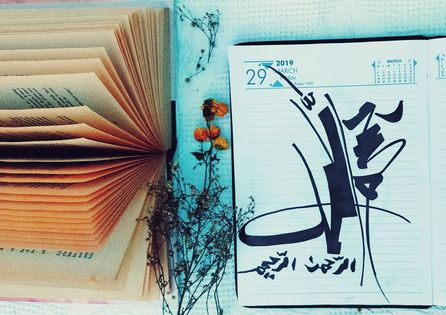

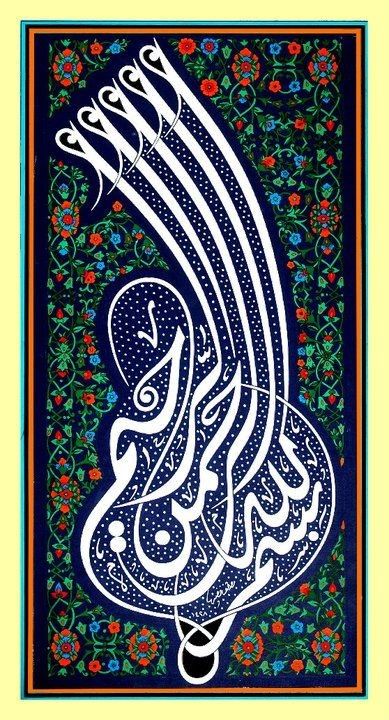

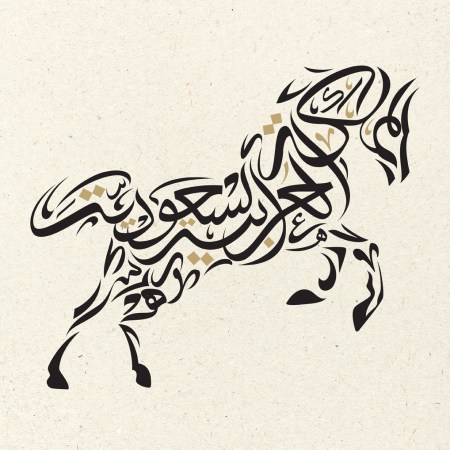

Calligraphy is one of the decorative arts and is often called the art of beautiful writing. Calligraphy occupies a special place in Islam and initially arose based on copying the Holy Qur’an. For this reason, the written word itself acquired a sacred meaning.

According to one of the hadiths, the Prophet Muhammad said: "Writing is half of Knowledge." In the medieval culture of the Crimean Khanate, the degree of mastery of the "beauty of writing", or calligraphy, became an intelligence indicator.

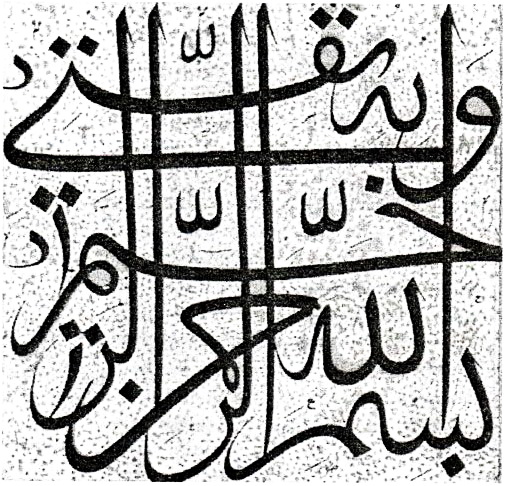

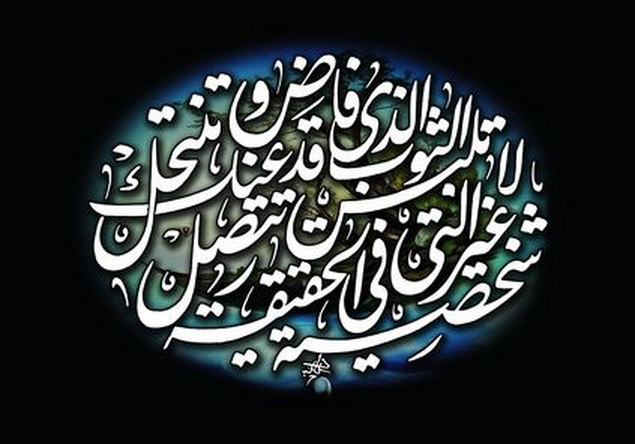

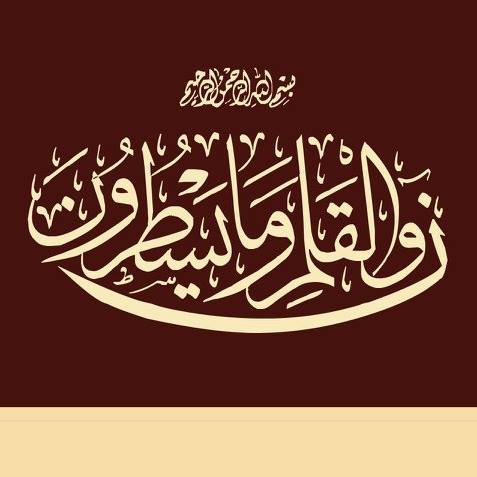

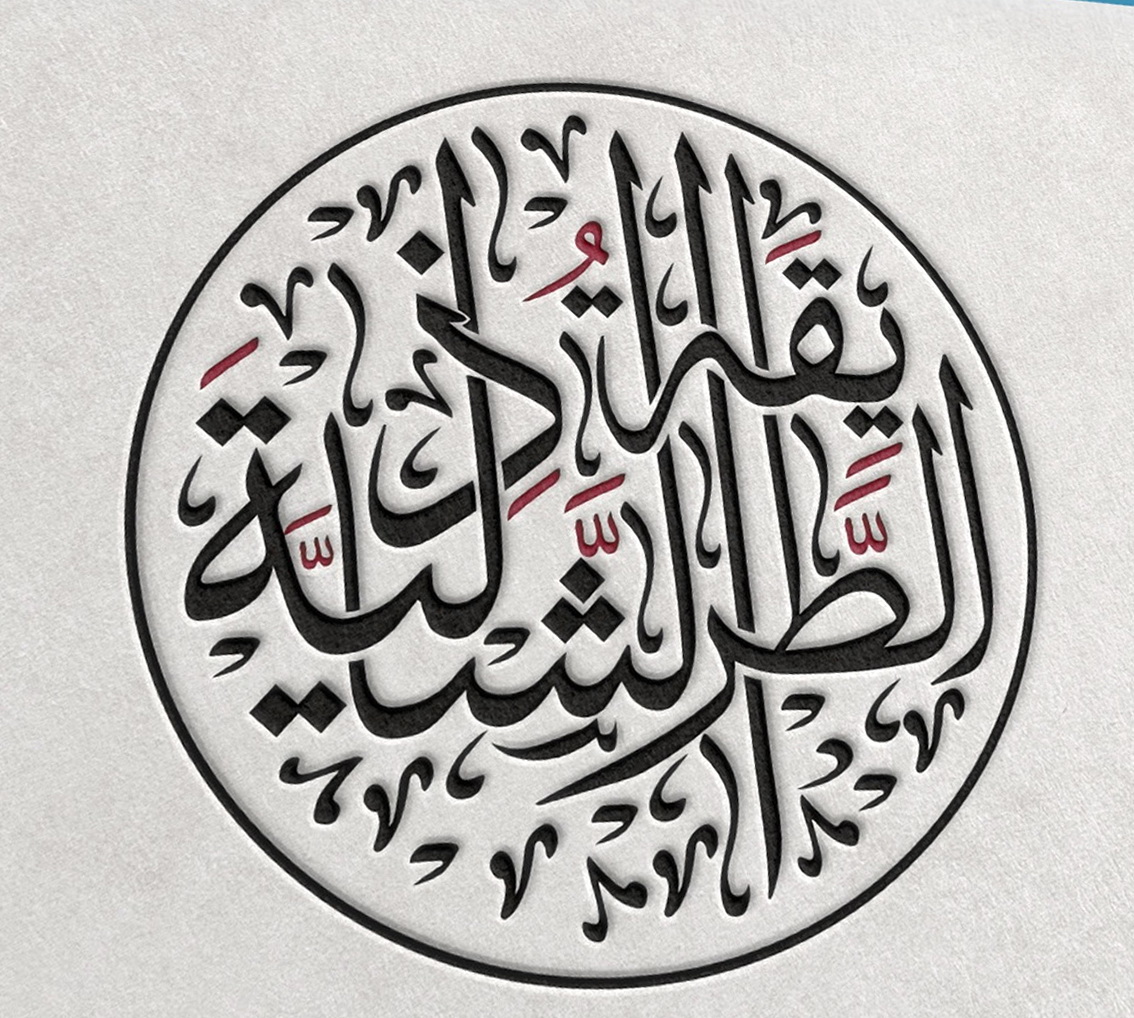

The early script, Kufic, which gravitated towards rectilinear, geometrized forms of letters, dominated Islamic calligraphy until the 12th century and was canonized as the script used to write the titles of the surahs of the Qur’an. At the end of the 8-9th century, the Naskh ("correspondence") script stood out and gained popularity among book scribes. It later became one of the "six styles" of classical Arabic writing along with other scripts.

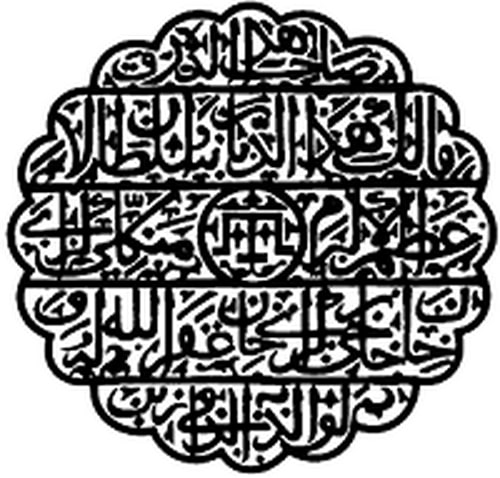

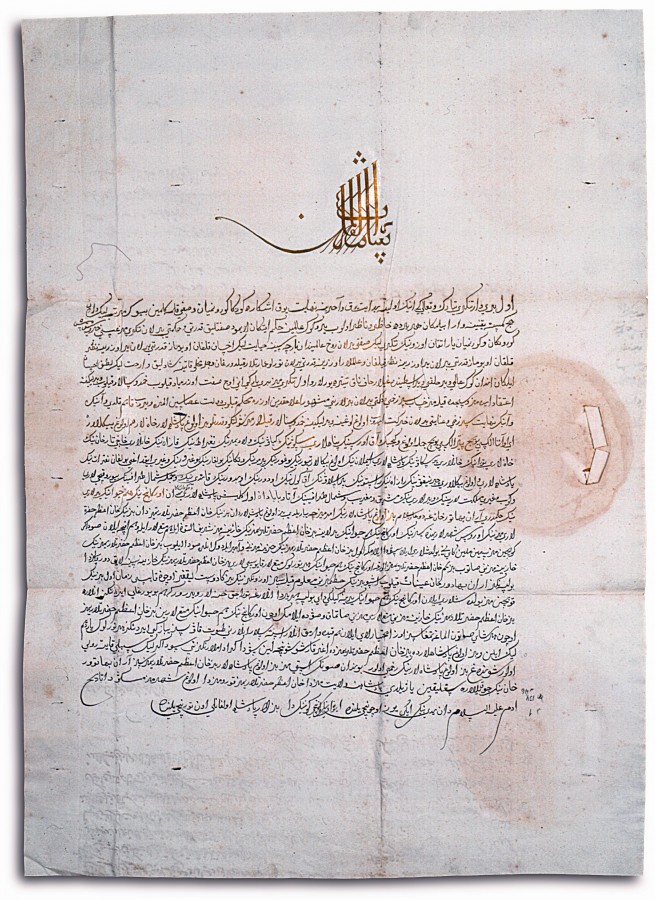

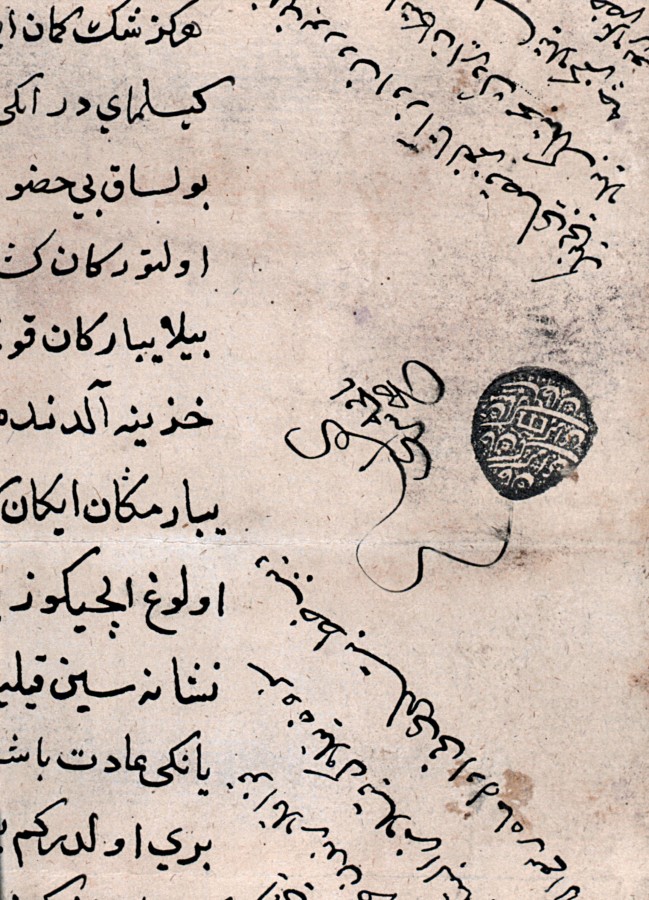

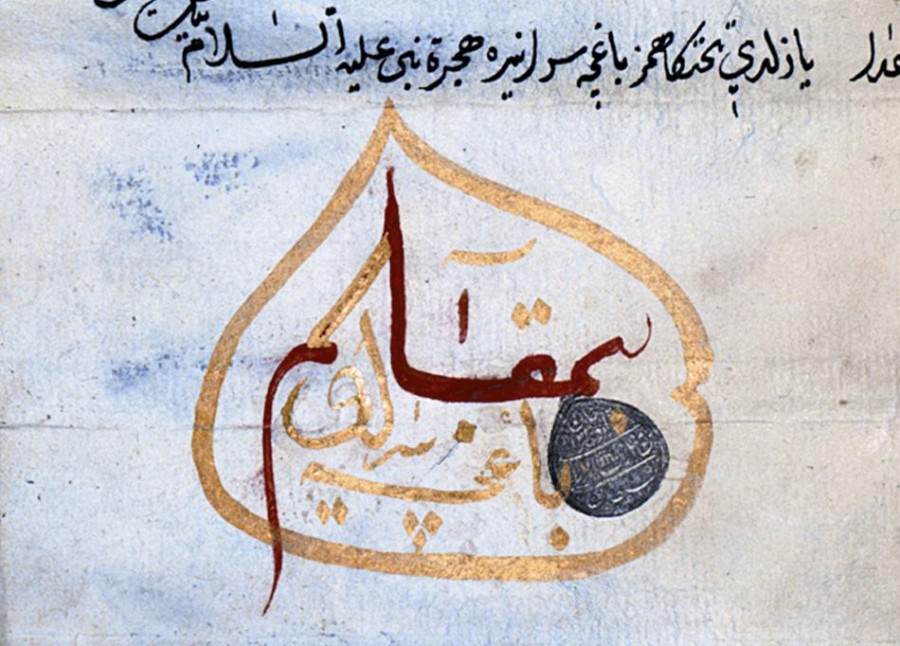

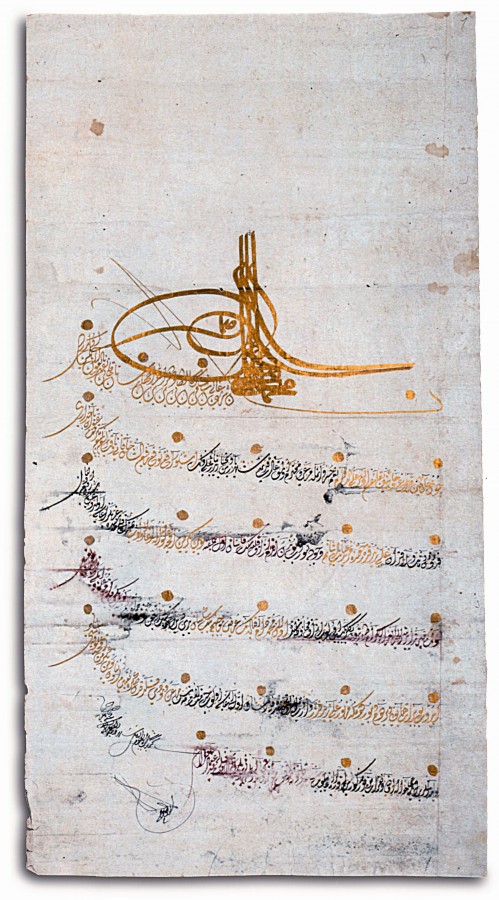

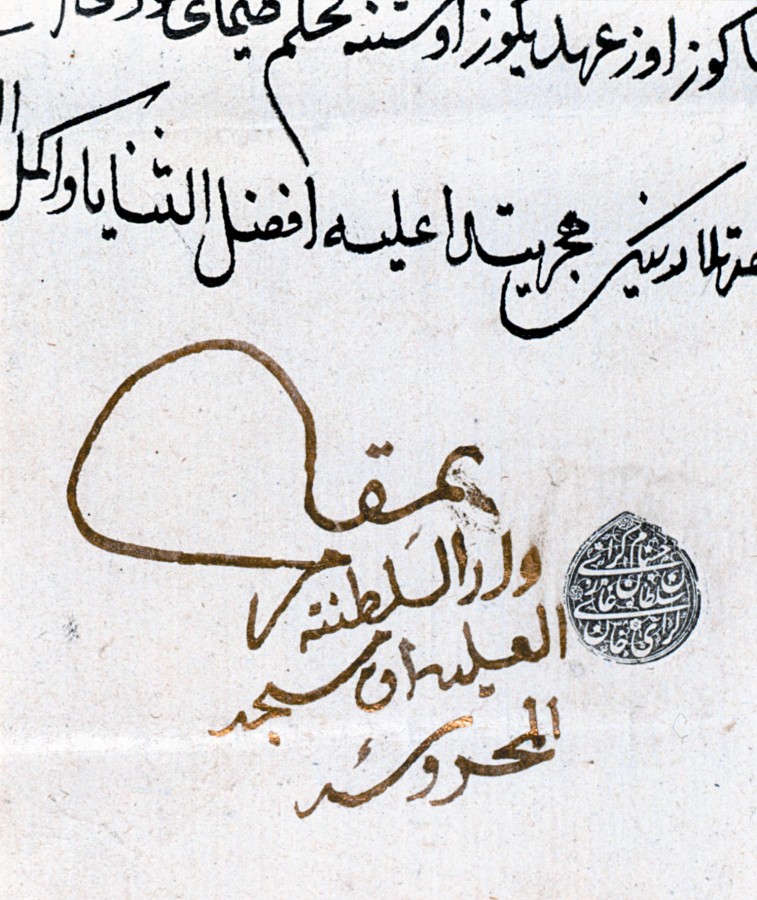

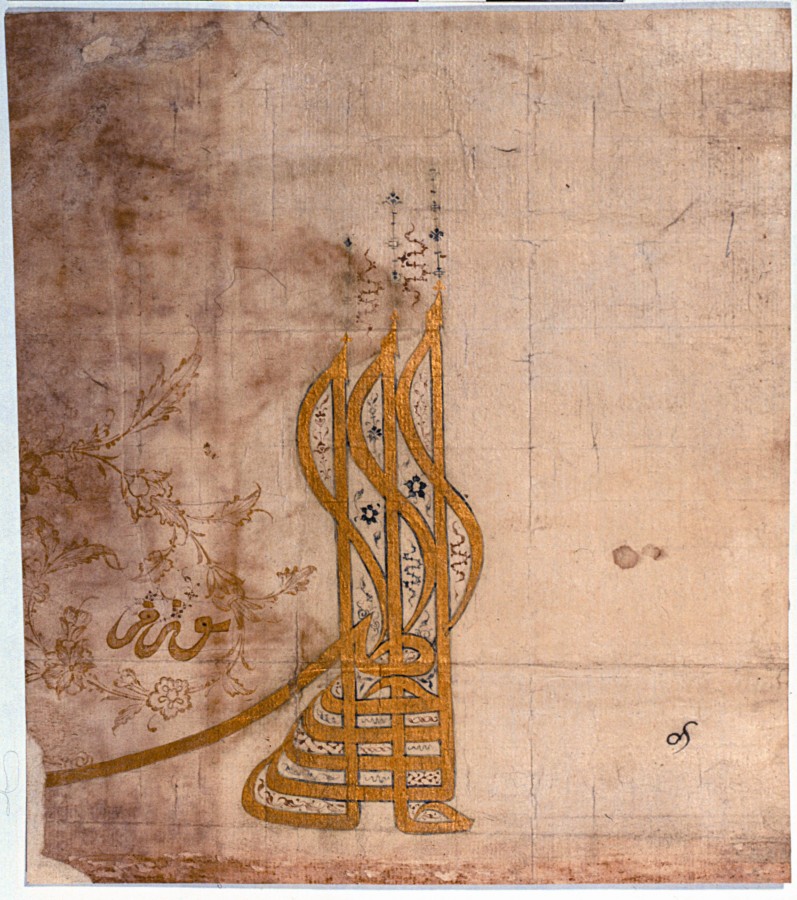

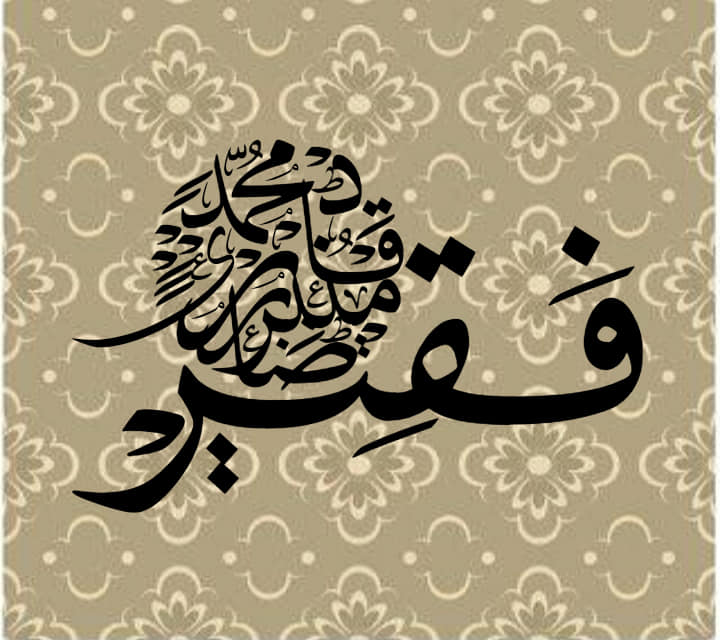

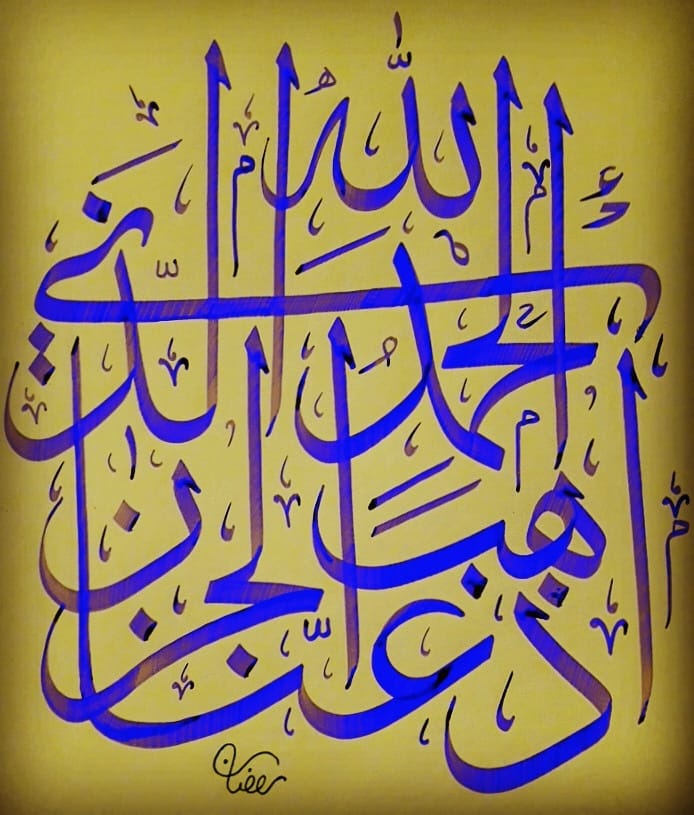

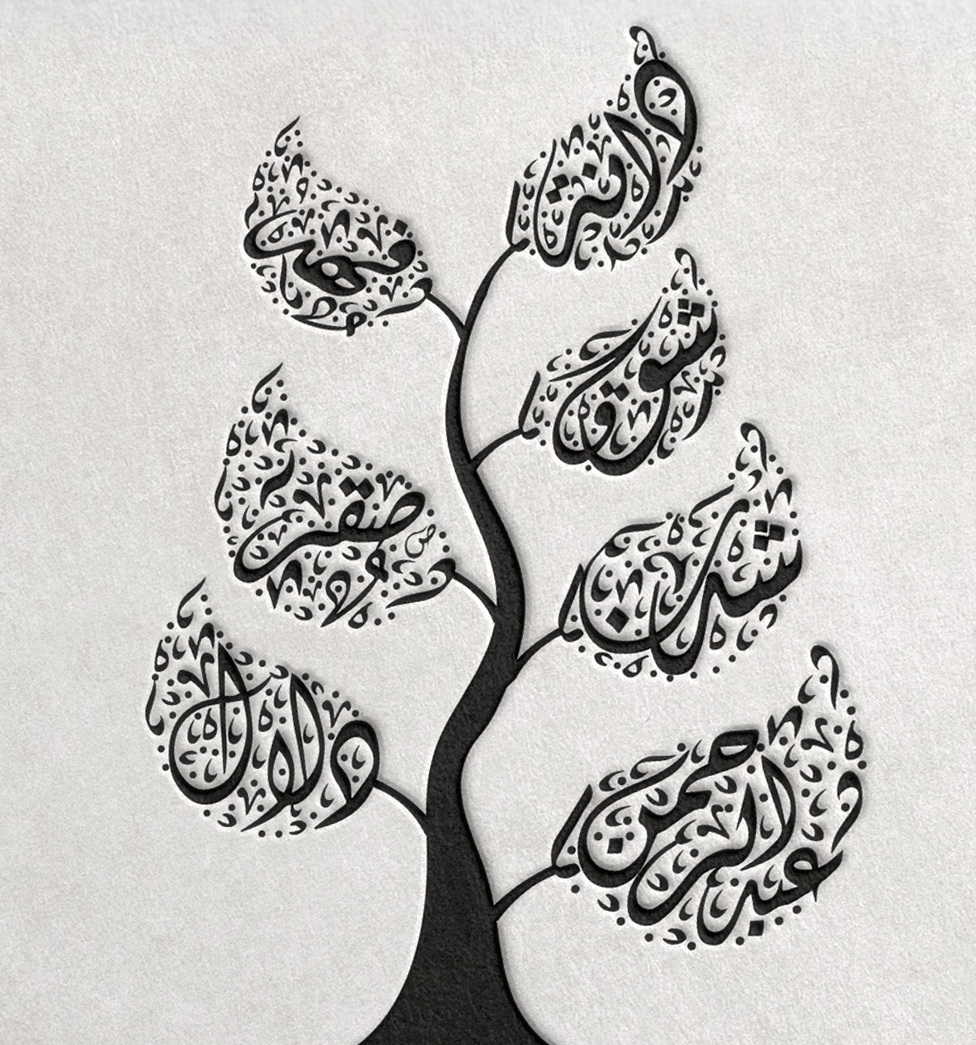

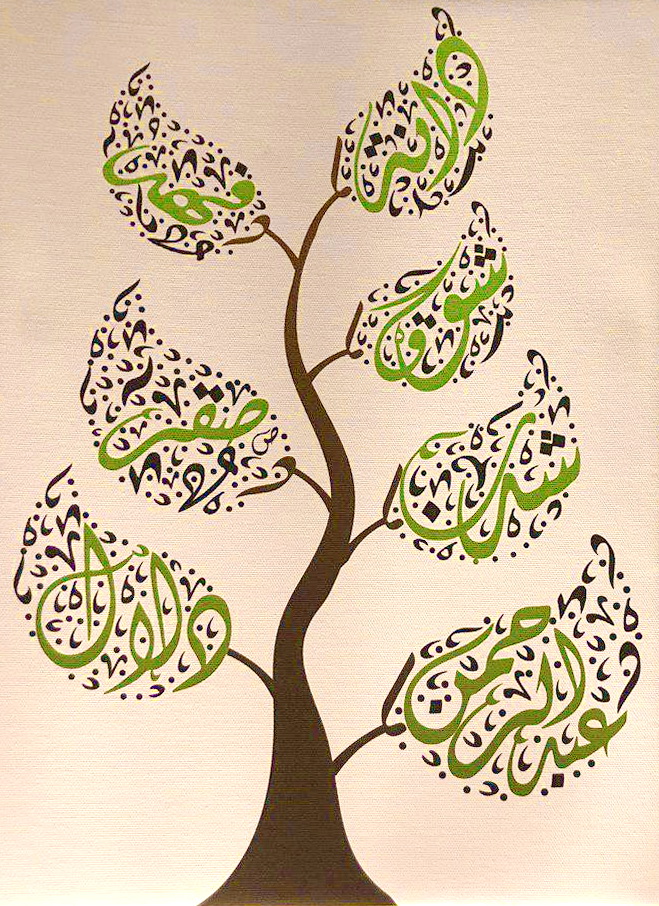

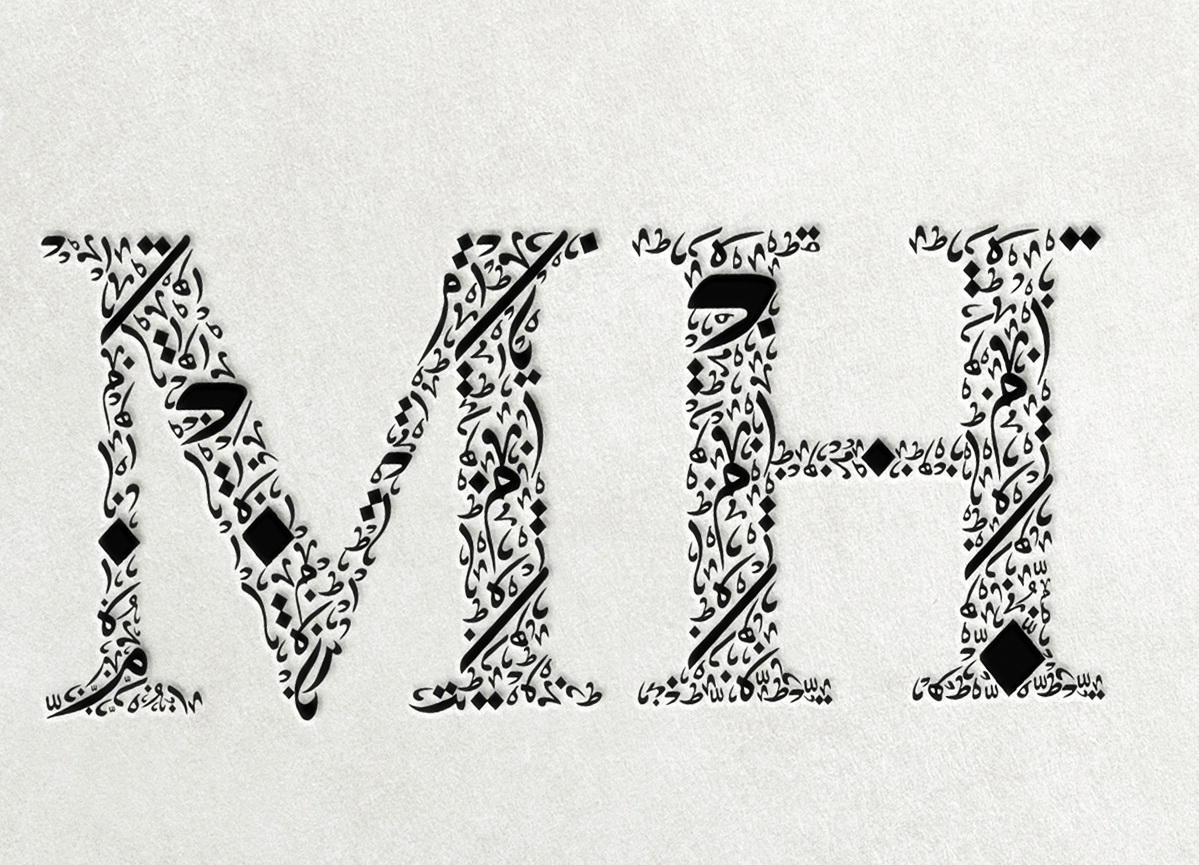

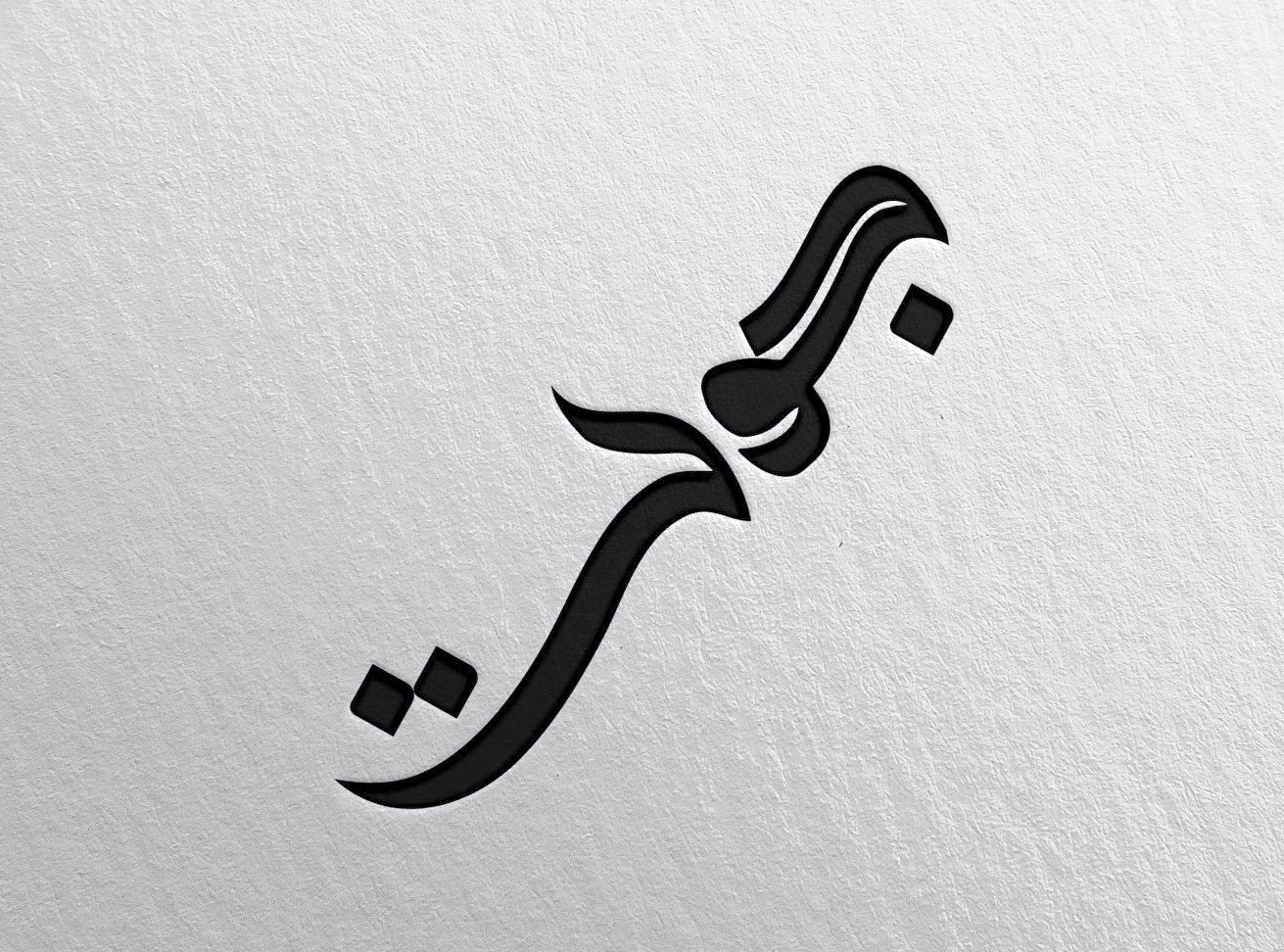

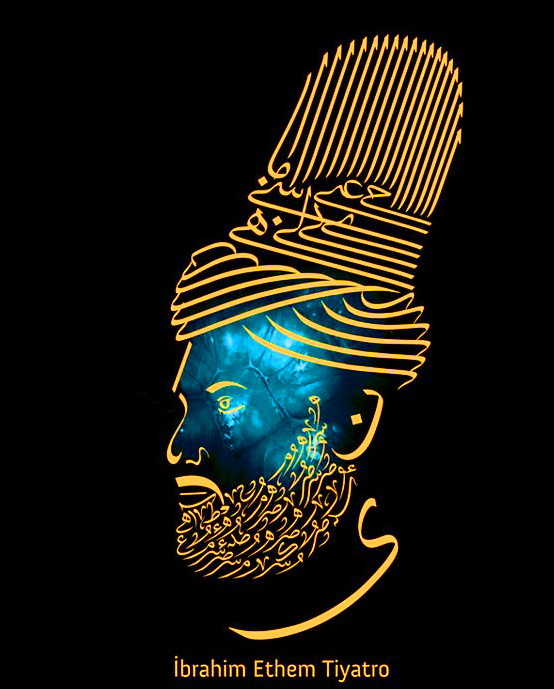

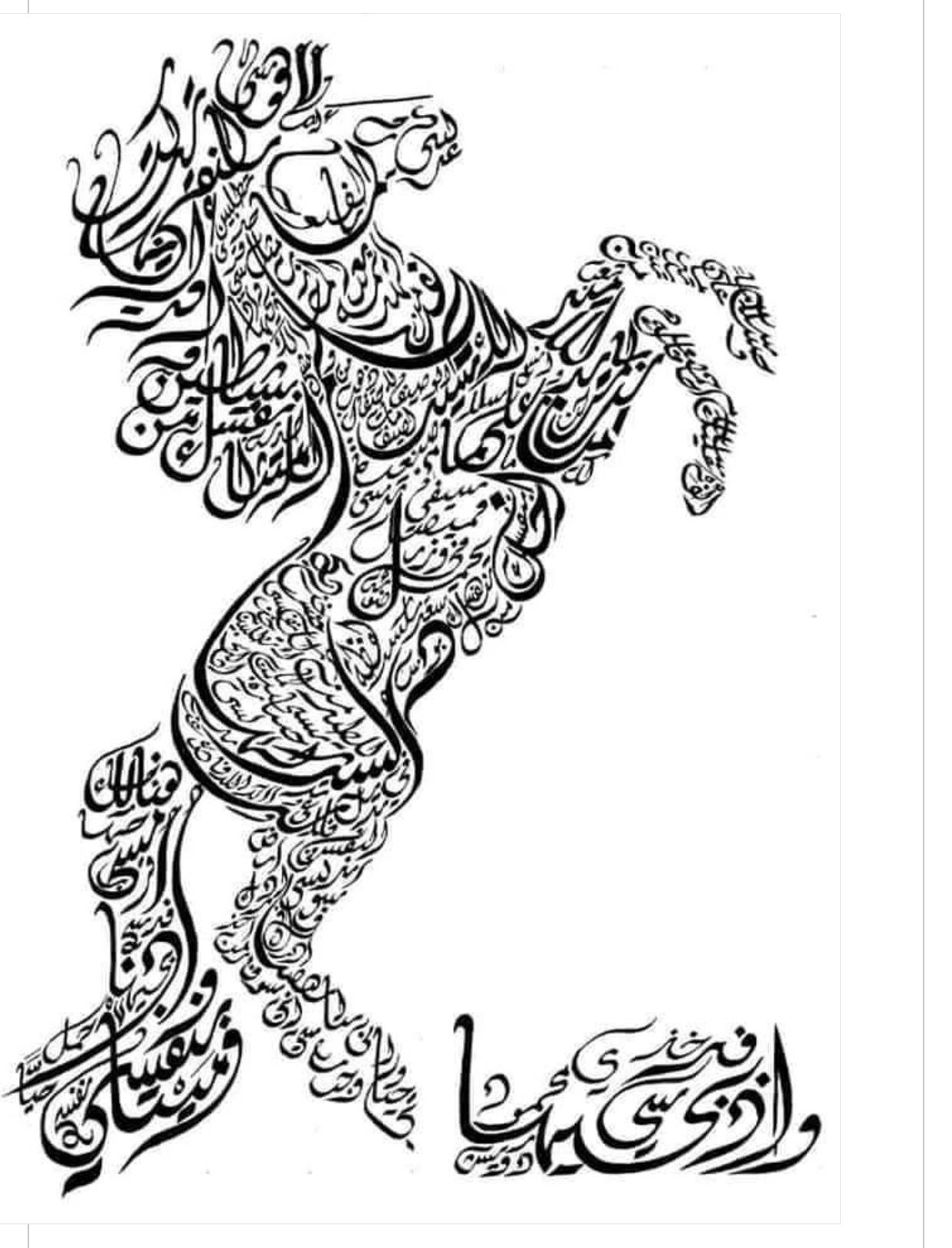

Muhakkak ("correct") was distinguished by the expressiveness of clear letters, and Raikhani ("basil") – by sophistication, which was compared with the delicate scent of blooming basil. In the solemn Suls ("one third"), curvilinear and rectilinear elements were correlated in a ratio of one to three. Tauki ("decree") was denser, and Rika was the most cursive of all scripts. The six writing styles were based on the system of "oral writing" - khatt mansub, invented by the Baghdad calligrapher Ibn Mukla (886-940). It is a system of proportions that determines the ratio of vertical and horizontal elements of letters in a word and a line. Based on classical Arabic scripts, Persian calligraphers developed new styles - Talik and Nastalik, which in turn gave birth to many decorative, exquisite scripts. In the 15-17 centuries, a peculiar genre of calligraphy, Kita, a sample of one or more script, spread across Turkey and Crimea.

The writing instrument was a kalam - a reed pen, whose sharpening method depended on the chosen style and traditions of the school. In one of the treatises of the 14th century, it is written: "The kalam is sharpened obliquely, and bear in mind that the tip of the kalam must correspond to the length of the thumb phalanx, but Baghdad scribes sharpen it along the length of the nail ...". The materials used for writing were papyrus, parchment and paper, the production of which was established in Samarkand and some other cities of the Muslim world. The sheets were covered with starch paste and polished with the crystal egg, which made paper thick and durable as well as the letters and patterns applied in colored ink - clear, bright, and shiny.

Calligraphy of the Crimean Khanate